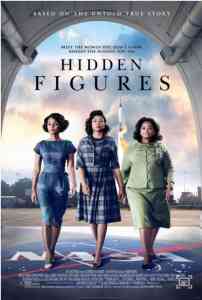

Movie Review: Hidden Figures

Theodore Melfi’s quest for the stars has all the rights cogs and gears as it features Taraji P. Henson, Octavia Spencer as Janelle Monáe mathemeticians playing a big role in the early days of NASA, but even with Kevin Costner’s booster rocket, the voyage feels mechanical

Hidden Figures

3/5

Starring: Taraji P. Henson, Octavia Spencer, Janelle Monae, Kevin Costner, Jim Parsons, Kirsten Dunst

Directed by: Theodore Melfi

Running time: 2hrs 7 mins

Rating: Parental Guidance

By Katherine Monk

The opening sequence shows three black women standing by the side of the road. A ‘60s model sedan with its hood open hisses with portent. It’s the late ‘50s and we’re in Virginia. A police car approaches. A stocky white officer eyeballs the three women with suspicion, and before you know it, you’re already imagining carnage, humiliation, and all variety of grotesque racist offences we’ve come to know via Hollywood and its latent desire to unburden its so-white-soul.

Surprisingly, the awful thing doesn’t happen. The three women have a moment of verbal communication with the law, and the scene ends with all three of them receiving a police escort to NASA’s Langley Memorial Research Lab.

From this moment on, you know Theodore Melfi’s Hidden Figures is not what you’re expecting it to be — a fact far more interesting than any of the historical truths offered up in a predictable broth that blends feel-good genre with “you-go-girl” attitude.

Based on the real life experiences of mathematicians Katherine Johnson (Taraji P. Henson), Dorothy Vaughn (Octavia Spencer) and Mary Jackson (Janelle Monáe), Hidden Figures is a dramatized version of little-known truth. Back before the first IBM computer became an integral part of the space race, newly created NASA needed to compute complex equations. In order to do so, they needed human “computers” — people who could sit down with a slide rule and an adding machine to figure out orbital speeds and launch mechanics.

It’s awesome to even conjure the idea of blasting into space using analog tools. Especially now, when the modern mind can barely tell time without the aid of a digital display on an iPhone. This retro-blast of technology played a crucial role in Ron Howard’s Apollo 13 as we watched scientists scramble to create oxygen scrubbers with tape and foam, and we get a similar thrill here as we witness the birth of the space program in the back of a brick warehouse.

Though much of the scene work is steeped in shallow, tacky formula, where characters have a habit of coming up with the perfect comeback and bad guys are inevitably whipped down with a well-choreographed crack, the material is still profound.

Anything that approaches humanity’s bid for space travel has to play to our nobler spirit, or as the press materials put it: “shoot for the stars.” The quest is rooted in our innate curiosity, our cumulative intelligence and also our flickering sense of the divine.

In other words, it has to transcend all our petty, earthly squabbles, and back in 1960, Civil Rights were still nothing more than a “dream” petitioned by Martin Luther King and Kennedy. For director Theodore Melfi (St. Vincent), America’s racist South offers the perfect backdrop to play out this story of racial transcendence.

Our three heroines are already working at NASA as mathematicians when we meet them — a fact that already puts them in a league of their own. Yet, they are still segregated from their white colleagues. Washrooms are labelled by race as well as gender, and all the African-American employees seem to be housed in a separate building.

Yet, when director Al Harrison (Kevin Costner) needs the best mind on campus, he’s greeted by the friendly face of math whiz Katherine Johnson, the best human computer in Virginia. Needless to say, she’s ostracized by the entire staff of white, male engineers who refuse to even share the same coffee pot.

Similar slights befall the other two women, both of whom possess their own brand of genius, but get no respect from the ruling white elite.

Imagine The Help meets The Right Stuff and you get a very good sense of which buttons and emotional thrusters director Melfi is using to guide his plastic model of a moon rocket. At times, it feels so fake and orchestrated that even Octavia Spencer’s ability to deliver any line with authenticity starts to rattle and hum. The same goes for Kevin Costner’s all-American heroism, which is exploited to the fullest, burning hot and enabling lift-off, but always feeling a little like character stereotype as a result of the wire and tortoise shell glasses. Even Jim Parsons’s (Big Bang Theory) geek factor feels like a branding exercise.

Of course it all works. Every piece in the emotional puzzle has been carefully crafted. Every wheel and cog turn with the precision of a Swiss time piece. It’s a work of skill, and it’s packed with powerful female role models who refuse to surrender to hate. But it also feels a bit mechanical, an emotional mainspring that’s wound without too much tension, and unwinds tick by tock, the quiet whirr of a well-behaved revolution that changed the white face of science with bold black figures.

THE EX-PRESS, January 7, 2016

-30-

No Replies to "Hidden Figures blasts into racist past"